Making Time. Collective Experiences of Time in Continuous Ensemble Practice

artistic research by DANIIL PILCHEN, NIRANTAR YAKTHUMBA, and GREGOR CONNELLY

Time perception is often seen as an exclusively personal and introspective experience counterposed with the clock-time of ‘objective reality’. However, through the practice of collective listening and playing, music can create powerful shared experiences of time and synchrony. These experiences are intuitively familiar to many musicians, and ensemble musicking offers unique environments for studying them.

We had an artistic residency at Studio LOOS in February–May 2023. It was focused on the composer Daniil Pilchen’s research project, Making Time Together. Collective Experiences of Time in Continuous Ensemble Practice. The results of the two workshops with the ensemble were presented in two concerts at Studio LOOS on March 3 and May 12, 2023. The workshops allowed us to develop innovative approaches to listening and explore their potential to influence listeners’ perception of time,

One particular kind of such listening experience is centred around the spatial awareness of the listener. Developing an intuition for interacting with the resonances between various spaces – strings, instrument bodies, resonant objects, the room in which we play – in connection with how that affects our experience of time became the core concern of these workshops.

This report will cover the technical and methodological aspects of our research into the creative use of what we call ‘boundary acoustic spaces’. In section 2, we will briefly describe the research goals with which we started this project, followed by the theoretical context and artistic background preceding it in section 3. Then, we will outline the planning and timeline of this project in section 4. Moving on, we will cover each of the two workshops separately, describing their starting points, methods used, outcomes, and the pieces that resulted from them in sections 5 and 6.

RESEARCH GOALS

We explored how the listening experiences of both the musicians and audiences can inform our further research into how we think about time in music. We collaborated closely with Studio LOOS, which provided the space for our experiments and concerts, and the necessary equipment.

Before starting the project, we formulated a set of research goals:

1.1. To explore how various modes of listening influence our experiences of time during the workshops and discussions between the composer and ensemble members.

1.2. To explore the potential for enhancing the degree of the performers’ participation in creating the pieces through ‘distributed creativity’: shifting the dynamics of the composer‑performer relationship by adopting changes to conventional music notation.

1.3. To make the possibility of musicians’ influencing each other’s listening a structural part of the compositions, thus allowing for creating common experiences of time within the ensemble.

1.4. To investigate the acoustic properties of the space during the workshops and research sessions. The various ways different spaces respond to sound influence the perceived durations of sounds in that space.

1.5. To develop compositional strategies that employ musicians’ awareness of the room’s acoustics as a foundation for the rhythmic structures of the pieces.

1.6. To investigate the potential for altering the perception of space using amplification techniques and resonating vessels.

RESEARCH CONTEXT

Our workshops and concerts revolved around Daniil Pilchen’s research titled Making Time Together: Collective Experiences of Time in Continuous Ensemble Practice. This research expands upon his previous artistic practice and research.

emergent time

Set in the highly ritualised context of a concert, musical time is separated from the time of everyday life. Framed by this ‘time of artistic perception’ (Zagny 2020: 11), music requires a specific temporal organisation. Composers usually approach this by creating particular models of time beforehand to be experienced by the listener at the moment of performance. Musical time, thus understood, is immutable, and listeners make sense of a sonic work by recognising the precomposed temporal patterns.

We aim to achieve a different dynamic through developing pieces that incorporate active listening at their core, and where the sound emerges from a listening body’s desire to communicate and is not assumed to happen by default. The time of the piece is thus constantly reinvented by listening performers, and the line between the performer and listener blurs, inviting the listener to enter the practice of creative listening on par with performers.

We develop a notion of musical practice being a broad and all-encompassing activity that affects, inspires, and structures one’s everyday life. It goes beyond a professional activity and invites a broader variety of expressions than the usual academic forms of music-making. This notion is inspired by such works as Christopher Small’s Musicking (Small 1998) and Eva-Maria Houben’s Musical Practice as a Form of Life (Houben 2019). For Houben, musical practice necessarily involves repetition without aim at a final product, and this aimless (hence potentially endless) repetition makes practice inseparable from everyday life (Ibid.: 31). This repetitiveness creates a special relationship between the practitioners, allowing new kinds of non-verbal communication to emerge, transforming their understanding of the world through acts of sonic performance (Ibid.: 10–11). Referring to these qualities of repetitiveness and aimlessness, hereinafter we will call this type of practice ‘continuous’.

There is a long tradition of establishing continuous collective practices. Such ones as Pauline Oliveros’s Deep Listening and many composers of Wandelweiser collective focus on exploring attention and modes of listening (Oliveros 1999), Éliane Radigue has been developing a practice of scoreless collaborative composition for the last 24 years (Nickel 2016). Many of these practitioners highlight the political potential of their way of music-making (Bauer 2020, Dougherty 2021). However, the current climate of institutionalised music production is often neglecting, and sometimes hostile towards, such collective practices. The gig economy of commissions and new music festivals is rooted in a larger neoliberal socio-economical paradigm perpetuating the violent myth of individualistic achievement. An essential part of this paradigm in the age of information capitalism is the idea of commodified time. If wealth is seen as liberated from material resources and supposed to grow indefinitely, an individual’s finite time becomes the only tangible resource. In our practice, we point to a reality in which time is produced through human interaction and listening.

Since 2019, Daniil has been working on Songs, a series of chamber pieces in which he has been exploring questions of musical time and musician interaction. The series was conceived as he developed his Master’s thesis titled Losing Time (Pilchen 2020). In his thesis, Daniil was concerned with the opposition between measured and immeasurable time and how they merge in antinomic temporal experiences in music. The primary outcome of that research was the development of strategies for musical interactions without external time measures. The human experience of time and the ability of music to shed light on it have since become the core concern of his practice. Since 2021, the development of the series has been heavily influenced by Daniil’s close collaboration with the Kali Ensemble, which ultimately led to the conception of this project.

collective experiences of time

Music creates powerful shared experiences of time and synchrony while playing and listening together. Such experiences are particularly intense when there is nothing to measure time against, such as a metronome or a stopwatch (Pilchen 2020). Although these collective experiences are intuitively familiar to many musicians, researchers are still mainly concerned with individual experiences (Voegelin 2010, Glover et al. 2019). We hypothesise that collective experiences of time are founded on the musicians’ ability to influence each other’s time perception through listening.

Research in various fields suggests that attention affects time perception in many ways. Philosopher Henri Bergson’s idea of ‘simultaneity of flows’ (1965: 52) presents time as a qualitative multiplicity when two durations are simultaneous as long as a third one – one’s perception – encompasses them both. In (1946: 189), he suggests sympathy as a way to understand duration, paving the way to Jean-Luc Nancy’s idea of ‘sonorous time’ of resonance (Nancy 2007: 13), suggesting the possibility of collective experiences of time through listening.

Neuroscience shows evidence that time perception is highly malleable, both by external stimuli (Eagleman 2009, Cai et al. 2012) and expectation (de Lange et al. 2018). Modern monitoring techniques show the ability of brains to synchronise (Babiloni and Astolfi 2014). Other sciences show more evidence for spontaneous interpersonal synchrony on different levels, from behavioural mimicry (Chartrand and Lakin 2013) to physiological synchrony (Palumbo et al. 2017, Mayo and Gordon 2020).

Using these inputs as starting points for the theoretical framework, we aim to develop a methodology for organising and analysing listening practices to generate knowledge of time. Listening has been discussed for its epistemic potential to create knowledge (Voegelin 2010, Feld 2015). Bijsterveld’s three-dimensional topology of ‘modes of listening’ (2019: 61–86) based on their purpose, way, and direction (why? how? and to what?), is particularly useful in our practice.

The question of collective experiences of time is particularly suited to be tackled through musical practice. For example, the potential of various listening modes to alter our temporal experiences can be relevant for a more general discussion about the relationship between attention and time perception. Establishing the link between awareness of the acoustic environment and the experience of time in musical settings can lead to a deeper exploration of the dynamic relationship between space and time.

the gift economy of time

Is time an emergent property of human consciousness or an objective physical phenomenon? While not attempting to give a definitive answer to that question, we point to the political consequences of these varying interpretations. If time is a product of our conscious effort and it is possible to affect each other's time experiences through collective listening practices, then, in playing music together, we are making and giving each other time rather than spending whatever time is already there.

If time emerges from a musical dialogue between listening and sounding practitioners, how to determine its value? This question invites a reimagining of the economy of music. Lewis Hyde contests the idea of ownership in arts and suggests that a work of art is more fit to exist in a gift economy than in property exchange (Hyde 2012: 160–161). He supports this argument by exploring anthropological research into gift exchange in various cultures. In gift exchange, the gift is not the material thing gifted but the act of gifting itself. Thus, the value of the gift rises the more it is given away. If time is seen as a gift, the activities seen as spending time in the paradigm of commodified time start making time instead.

These two approaches to time – as a gift or a commodity – are mutually exclusive, and both have different consequences for the broader musical practice and the way we see time in our everyday lives.

The current understanding of time as a commodity has detrimental consequences for general musical practice, particularly for composed music. Presuming that time is always already there as a container we fill with sounds obstructs the listener’s ability to create their own temporal dimensions (Voegelin 2010: 124). Rejecting the commodification of time in favour of creating the conditions for gifting time will make more playful and imaginative ways of working with time possible in composed musical works.

Bergson connected the idea of time as a property of consciousness to the possibility of free will (1913). The heterogeneous and indivisible nature of his time-duration of conscious states does not allow predicting the act by its antecedents, thus denying ‘the very idea of necessary determination’ (Ibid.: 239). Can we take this argument one step further, from individual free will to collective self-determination? If time is not external to us, then there are infinite possible futures we can actuate, and there is hope in this uncertainty.

Art, being an inalienable part of everyday life, can shape how we think about reality and point at possibilities of conceiving this reality differently. In Noise, Jacques Attali challenges the prevalent in the history of music notion that music merely follows the economic transformations of societies in which it is made (Attali 1985) and points at its possibility ‘to foreshadow new social formations in a prophetic and annunciatory way’ (Jameson 1985: xi). We hope that the new ways of thinking about time discovered in musical practice will find their way into the lives of practitioners, listeners, and people around them, inviting a more radical reimagining of labour, culture, and the role of interpersonal relationships in the production of values.

PLANNING

The residency consisted of two workshop periods of two weeks each. Each workshop was divided into two stages. The first stage contained several research sessions in which the composer Daniil Pilchen and members of Kali Ensemble Nirantar Yakthumba and Gregor Connelly worked on acoustic measurements of the space and figured out the placement of microphones, speakers, and instruments to use the space creatively and turn it into an instrument in its own right. The second stage was the rehearsals when the rest of the ensemble – Giuseppe Sapienza (clarinet), İdil Yunkuş (violin), and Beste Yıldız (cello) – joined. Both workshops culminated in concerts at which new large-scale compositions were premiered.

FIRST WORKSHOP

During the first workshop (February 14–March 3), we mainly focused on investigating the dynamic relationship between space and our experience of time. Our research sessions involved measuring the frequency response of different parts of the room and figuring out how to use the space creatively and turn it into an instrument in its own right. Once the rest of the ensemble joined us for the rehearsals, we started exploring the relationship between acoustic awareness and different listening modes and their potential to influence the musicians’ and listeners’ temporal experiences.

methodology

We used various methods to address our research goals, combining acoustic analysis and measurements, music composition, and music rehearsal and discussion practice.

acoustic analysis of the room

Figure 1: blueprint + feedback points map

We started by exploring the blueprints of the space that Peter van Bergen from Studio LOOS provided to us. At first, we used it to make a tentative map of the most prominent room modes using amroc, an online room mode calculator (amcoustics n.d.). We used it to calculate the axial modes when taking the room’s dimensions from the blueprint as input. We assumed that the actual modes would differ from the ones calculated in amroc since the room isn’t completely symmetrical: it has a protrusion on one side and two wide pillars in the middle of the room. However, upon comparing amroc calculations with our measurements in the space, we realised that they were quite close to one another. We mapped out our actual measurements of the room modes on the blueprint and used them to decide which two points to choose for the placing of our feedback systems (see points 1 and 2 in Figure 1; points 3 and 4 were added during the second workshop).

First, we measured the critical distance between the microphone and the speaker (Genelec 8020). Upon experimentation, we figured out that as long as the microphone is 1.5–2 meters away from the speakers, our measurements were correct since they corresponded to prior calculations.

Figures 2&3: prominent frequencies spectra in points 1&2

Afterwards, we started analysing the frequency responses of the chosen points, hoping for the results to be contrasting, which would support our artistic idea, which was to have a scale of frequencies for the instrumental parts which would allow each musician to excite different parts of the room, making their sound audibly ‘travel around’ the audience.

We first tried recording sine sweeps and then convolving them with their inverse in Praat, a spectrum analysing program (Boersma and Weenink 2023). However, Gregor realised that a more empirically effective approach would be to use feedback sweeps instead of sine sweeps since in that case, the space generates the frequencies itself instead of reacting to a signal. To achieve this, he sent the measurement microphone’s signal to a narrow-band bandpass filter, which he had automated in Logic Pro (Apple Inc. 2023) to sweep from 30 Hz to 3500 Hz. We didn’t go higher or lower because we were only interested in the playable range of our instruments. This was sent back out through the speaker to create a feedback loop. By adjusting the gain and compensating the increase in gain with compression to tame the louder resonances, we could control how rich our spectrum was.

In the end, the result of the analysis proved that the frequency response of these two points was contrasting, as was predicted by our calculations. However, we hypothesised that recording feedback sweeps at any two arbitrary points would give us sufficiently contrasting results simply because of the complexity of the room’s acoustics. This hypothesis was to be tested during our second workshop.

composing music based on the results of the acoustic analysis of the room

Figure 4: A page from the score of SONGS OF DESPAIR, RAGE, AND HOPE

We figured out that each point in the room produces a different frequency response. which would prove useful in our work. After analysing the feedback sweeps, we further limited the range of usable frequencies to 50–950Hz. This was the most realistic range that could be excited using harmonics on the piano, and we wanted the rest of the instrumental parts to fit in the same range.

The pitch material in several parts of the piece was derived from the analysis of room modes. Specifically, in the first two movements, the piano part consisted exclusively of harmonics that were the closest approximations of the prominent room modes. Similarly, the lowest two strings on the cello were tuned such that certain harmonics of these two strings matched the room modes. The clarinet and violin approximated the room modes within a sixth of a semitone.

Daniil composed the piece using the outcomes of our acoustic analysis. One goal of the composition was to create a hybrid space in which the instrumental parts could affect the acoustic perception of the room. An important aspect of such an approach was the use of feedback to build reciprocity between the instruments and the surrounding room. This allowed the musicians to extend their sense of instrumentality to the space.

The piece comprised nine parts (five Songs with the whole ensemble, two interludes, and two solos), each suggesting a different perception of space.

Figure 5: the structure of the piece

building hybrid spaces (instruments+ feedback systems)

In the first two parts, the instruments were amplified. However, we routed their sounds through the ‘feedback systems’ (Genelecs and microphones at points 1 and 2) instead of the PA. As a result, whenever one of the instruments would excite a frequency that the room would respond to at one of those points, listeners would hear sustained feedback. Since these two parts mostly consisted of decaying sounds produced by plucking strings or exciting harmonics on the piano, the feedback in the room extended the sound’s decay time. We added artificial reverb to the sounds produced by the instruments to allow more time for the feedback loops to start without increasing the gain to uncomfortable levels.

In the subsequent four parts (Songs III–IV and the Interludes), the instruments were not amplified. Therefore, the space sounded much dryer and ‘smaller’ than before. To emphasise that difference, we raised the noise floor of the room by playing back pink noise very softly through LOOS’s 8-channel PA system. This was done to reduce the perceived decay time of the sound – thus making the room sound even ‘smaller’ – without being perceived as artificial noise.

Finally, the last three parts were focused on very strong feedback in the space and the instrumentalists interacting with it in real time. The two solos (clarinet and piano) were based on the interaction between a musician on stage and Gregor who was controlling the feedback systems via a Max patch (Cycling ’74 2023).

See the breakdown of amplification settings part by part in Figure 5.

developing an intuition for interacting with the acoustic characteristics of the space

The two solo parts – clarinet with feedback and piano with feedback – focused not only on interaction between the instruments and space but also on active listening both from the musicians on stage and Gregor, who was operating the electronics in front of the stage.

In the clarinet solo, Gregor was slowly moving narrow-band filters, and Giuseppe was trying to match the frequency he was playing with the feedback he was hearing. Since the range in which he was tuning was so narrow (433–495Hz), it was sometimes easier for Giuseppe to recognise where the sound was coming from in the space rather than the precise pitch. That way, he developed a way of playing which organically involved triggering responses in different parts of the room.

The reverse of this configuration was employed in the piano and feedback part. Nirantar performed a semi-improvisatory solo based on harmonics closest to the frequency response of the room. The general melodic outline of his solo spread from the centre of 434Hz towards the extremes of 138 and 719Hz. At the same time, Gregor was listening to Nirantar’s part and trying to match his frequencies with the narrow filter bands of the two feedback systems to generate feedback in matching registers.

imaginary spaces and memory games

Figure 6: page from for two soloists and ensemble

Another aspect of our research was the exploration of introspective modes of listening based on memory and imagination and investigating how these virtual spaces expand the physical and how they affect the way we listen to one another.

One way of doing this was introducing the elements of the imaginary into our ensemble practice through Daniil’s piece for two soloists and ensemble. Every rehearsal, we would spend around half an hour practising this piece, choosing a different pair of soloists each time. The soloists were asked to nod twice during the piece, one nod physical, another imaginary. The ensemble was invited to sound when the imaginary nod happened. At first, this instruction seemed impossible to follow, but after playing the piece several times, we developed a practice of intensely attentive listening and reflection, in which the ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ times became intertwined. We didn’t end up performing this piece at the concert, but it still affected the build-up of our practice through the introduction of improvisation, imagination, and intense listening to one another, and thus reflected in our final performance.

Another way was what we called ‘memory games’. They consisted of memorising certain parts of the score and repeating them over different intervals in different instrumental configurations. We have tried many different versions of ‘memory games’ during the rehearsals and developed them as a practice in parallel with imaginary listening. In the final piece, the memory games served as two interludes. The first was the violin solo based on remembering Song I, and the second was the tutti based on Song II (see Figure 5).

Outcomes

room mode calculations

During this workshop, we found that calculations made with amroc were consistent with the experimental results despite irregularities in the room’s shape. This might be useful to know when there is not as much time to spend measuring the space as we had during this workshop. Calculating room modes using the dimensions of a given room can be a reliable source of data for a music composition even when a composer does not have access to the space.

Furthermore, we found that, while a traditional impulse response or sine sweep gives a more complete picture of the frequency response of a room, a more empirically straightforward feedback sweep is sufficient for our artistic purposes, which consists of the use of the most prominent frequencies as a basis for the pitch material of the piece.

distance between the microphone and speaker

We discovered that the critical distance between a microphone and a speaker should be 1.5–2 meters for a reliable feedback sweep to analyse the frequency response of a space at a given point.

arbitrary points

During our experiment, we selected two points in the room that had contrasting room modes based on our calculations. After testing, we observed that the frequency responses of these two points were significantly different. However, the room mode patterns in both cases were so complex that we began to speculate whether selecting any random points in the room could give us similar artistic results (i.e., contrasting spectra). This is something we plan to investigate further in the next workshop.

the piece

The main outcome of the first workshop was the piece SONGS OF DESPAIR, RAGE, AND HOPE (Pilchen 2023a) that we presented at the concert on March 3, 2023. This piece combined two of our research focuses for the residency.

Firstly, the acoustic properties of the performance space were highlighted with feedback, allowing for stretching the sounds’ decay time. The pitch material was based on the room’s frequency response, measured in a series of acoustic tests done in the space prior to the piece’s composition. Secondly, we explored approaches to organising a musical practice beyond notation, such as guided improvisation, games, and mnemonics.

Figure 7: the performance of SONGS OF DESPAIR, RAGE, AND HOPE on March 3, 2023

SECOND WORKSHOP

During the second workshop (April 29–May 12), we expanded on our ideas from the first round, doubling the number of feedback systems and introducing four resonating glass vessels into the space, which were to be excited by transducers. The sounds of the instruments were sent through the feedback systems and the vessels. The vessels themselves were amplified through LOOS’s quadraphonic PA system. Building upon the outcomes of the first workshop in February and March, we continued exploring the temporalities that emerge in the resonances between various spaces and the ways we listen to them.

Some of our plans for the second workshop had to be adjusted following the changes in the ensemble configuration. Due to personal reasons, İdil Yunkuş (violin) and Beste Yıldız (cello) could not participate in this round of the residency. We decided that Daniil should play the violin part himself because he is a professional violinist and he already knew the part. To replace the cello part, we invited Maria Alejandra Bejarano Salazar on the double bass. The change in the instrumentation was justified by Alejandra’s excellent musicianship and her previous working experience with Daniil. These changes led to some adjustments in the final piece as well. Since Alejandra had just joined our practice and Daniil had not participated in the project as a performer before, we decided to reduce the number of ensemble parts from six to three and have more emphasis on solo movements with electronics.

methodology

In this workshop, we used the same methods as the last time with a few differences described below.

resonating vessels

The main difference between this workshop and the preceding one was the addition of four large resonating glass vessels into the space. Their purpose was to add four more different ‘spaces’ with their own frequency responses within LOOS and filter the instrumental sound through them, thus highlighting the idea of ‘hybrid boundary spaces’.

In the end, we only used the vessels in the first part of the piece, the double bass solo performed by Alejandra Bejarano. A transducer was connected to each vessel. The double bass sound was picked up with a condenser microphone and played back through the transducers and vessels. Since most of the acoustic energy remained contained inside the vessels, we decided to amplify them. A dynamic microphone was positioned inside each vessel. The sound from each vessel is amplified through one of the four PA speakers. To avoid feedback, we assigned the sound of each vessel to the speaker located the farthest away from it.

Figures 8–11: resonant vessels

arbitrary points

Following the prediction, we came up with during the first workshop, we chose two more arbitrary points in the space to analyse their frequency responses (points 3 and 4 in Figure 1). We skipped the calculation stage. We went directly to record the feedback sweeps at those points and analyse the response. As expected, the response of each new point was unique both compared to each other and the previous two points.

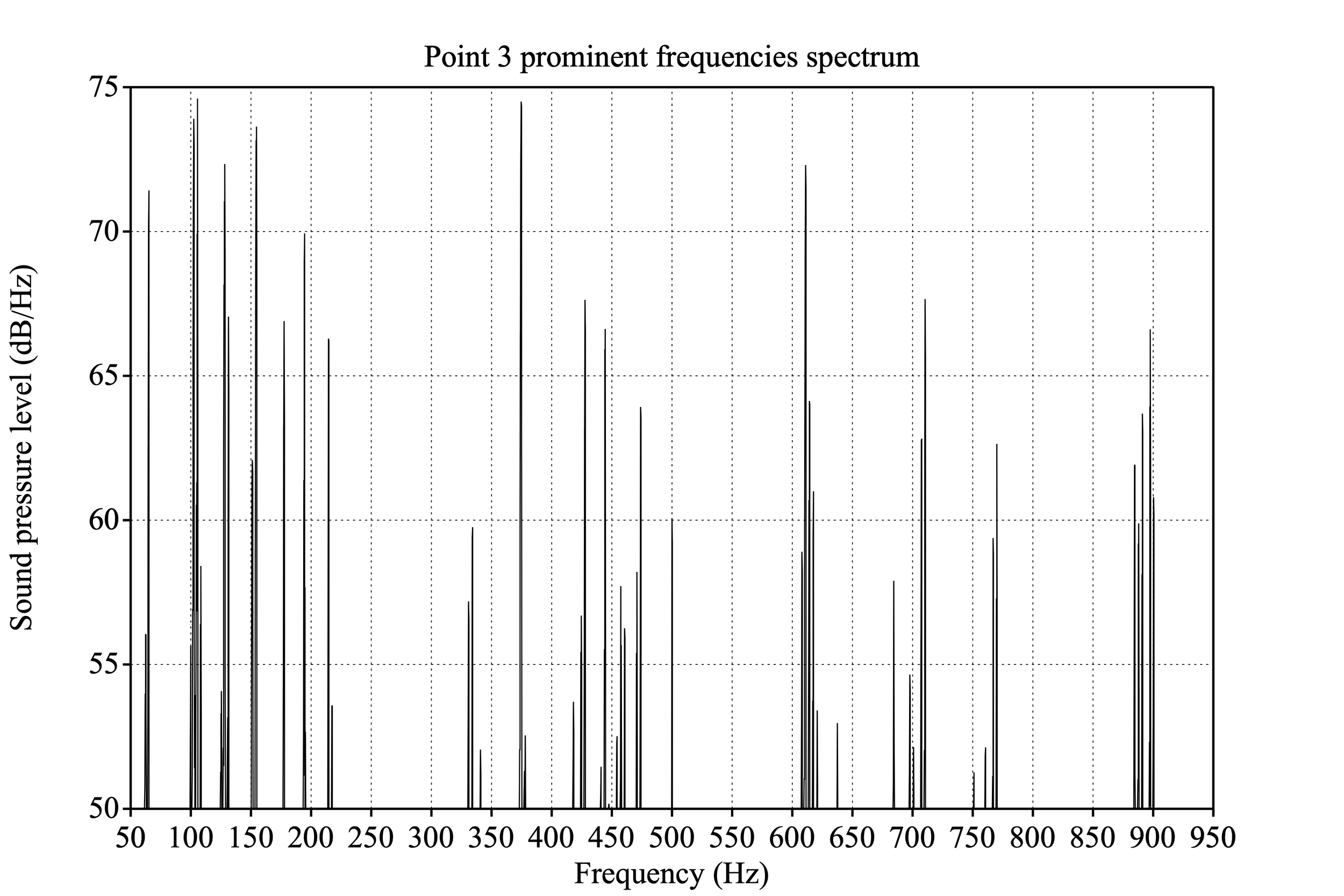

Figures 12&13: prominent frequencies spectra in points 3&4

Figure 14: all four points

doubling the feedback systems

Figure 15: complete setup for BOUNDARIES

After choosing two more points and recording the feedback sweeps on them, the rest of the methods were the same as the last time: we analysed the spectra using Praat, limited it to the range of 50–950Hz and used the resulting frequencies to create the pitch material for the piece.

This, however, led to some interesting results that affected our artistic decisions. First, having more feedback points in the ensemble Songs significantly heightened the effect of prolonging the instrumental sounds’ decay, because twice as many frequencies could be excited by the instruments. That way, we did not need to use additional reverb anymore and the gain level could stay the same.

In the clarinet solo, we had twice as many different frequencies while staying within the same range. Thus, the movement took twice as long and it was much more difficult for Giuseppe to find some of the frequencies because of how close to one another they were. Having the feedback come from four different points also allowed for more complex spatialisation.

This, however, led to some interesting results that affected our artistic decisions. First, having more feedback points in the ensemble Songs significantly heightened the effect of prolonging the instrumental sounds’ decay, because twice as many frequencies could be excited by the instruments. That way, we did not need to use additional reverb anymore and the gain level could stay the same.

In the clarinet solo, we had twice as many different frequencies while staying within the same range. Thus, the movement took twice as long and it was much more difficult for Giuseppe to find some of the frequencies because of how close to one another they were. Having the feedback come from four different points also allowed for more complex spatialisation.

Outcomes

arbitrary points

During this workshop, we confirmed the prediction we had after the previous one that picking any two arbitrary points in the space will produce contrasting spectra when recording a feedback sweep due to the complexity of the room modes present at each point. Our next goal will be to test this at other locations using the procedure that we developed during this residency.

developing a procedure for acoustic analysis

Completing the second workshop helped us finalise our procedure for acoustic measurement of spaces we plan to test at other locations. It is a simple procedure consisting of 4 steps:

a) picking several arbitrary points,

b) setting a ‘feedback system’ consisting of a microphone and a speaker 1.5–2 metres away from each other

c) recording a feedback sweep within the usable frequency range

d) analysing the frequency response of the point using Praat

resonant vessels and hybrid spaces

In this workshop, we have introduced the resonant vessels into our work and demonstrated the potential of combining different acoustic spaces into one ‘hybrid space’. Despite producing an artistically satisfactory result, we have only scratched the surface of what is possible to research in this area.

It is possible to apply the procedure described in the previous section to analyse each vessel and use these data to develop more specific relationships between them and the spaces where they are present. We will investigate this potential in more depth in our future projects.

the piece

The main result of the second workshop was a piece called BOUNDARIES (Pilchen 2023b). It owes its name to the attention to the spatial, temporal, and inter-relational boundaries which are the subjects of the piece. The piece can be broken down into four parts.

Figure 16: from the performance of BOUNDARIES on May 12, 2023

Figure 17: Alejandra Bejarano performing the double bass solo with vessels

The first part was a double bass and electronics duet, in which Gregor filtered the sound of the double bass through the four glass vessels in the room amplified by a quadraphonic speaker system. He was playing with the bandwidths and centre frequencies of the filters that were processing the sound sent to the vessels, highlighting different overtones, which in turn informed Alejandra’s playing, creating an interaction in which they both had partial control over the outcome of the sound.

The first piano note signalled the start of the second movement. In this ensemble movement, the musicians reacted to the decay of each other’s sounds. Each sound was extended by room resonances through the feedback systems. Sometimes, a feedback resonance would extend a note in such a way that it was unclear whether it was prolonged with feedback or played by an acoustical instrument. This was especially the case for the clarinet, as its spectrum was the closest to sounding like sine tones.

Figure 18: Gregor Connelly and Giuseppe Sapienza performing their duet

The third part was a duet between Gregor and Giuseppe, in which the latter tried to get as close as possible to the frequency of specific room resonances that were very close to each other. For example, the first frequency was 495 Hz in one feedback system. As he played, Gregor would send the clarinet sound to the specified speaker, activating the feedback. The closer the clarinet got to the frequency, the slower the beat frequencies were, which is how he tuned to the space. Once Giuseppe got the frequency right, they would nod at each other and move to the next frequency. This ended up lasting a whole third of the entire concert, and they only moved from 495 Hz to 435 Hz.

This part was followed by another ensemble part for violin, double bass, and piano. All their pitches and the frequency response of the feedback systems were set between 433 and 435 Hz.

Figure 19: Nirantar Yakthumba performing the piano solo

After this short part came the last duet, between the piano and electronics. Nirantar’s score consisted of four lines that corresponded with the resonances of each feedback system. Each system started around 435 Hz and would gradually move to another frequency by the end of the piece. Gregor’s performance revolved around listening to the harmonics that were emphasised by the piano, guessing which feedback system had that resonance, and reproducing that frequency in the feedback system by adjusting the parameters of the bandpass filters. Thus, it was the opposite of the duet with the clarinet and electronics. It required focused polyphonic listening from Gregor to be able to map the frequencies of the piano to the appropriate feedback system. He controlled very narrow bandpass filters (Q = 20) in a Max patch with faders on a Korg nanoKontrol.

This part was followed by another ensemble part for violin, double bass, and piano. All their pitches and the frequency response of the feedback systems were set between 433 and 435 Hz.

After this short part came the last duet, between the piano and electronics. Nirantar’s score consisted of four lines that corresponded with the resonances of each feedback system. Each system started around 435 Hz and would gradually move to another frequency by the end of the piece. Gregor’s performance revolved around listening to the harmonics that were emphasised by the piano, guessing which feedback system had that resonance, and reproducing that frequency in the feedback system by adjusting the parameters of the bandpass filters. Thus, it was the opposite of the duet with the clarinet and electronics. It required focused polyphonic listening from Gregor to be able to map the frequencies of the piano to the appropriate feedback system. He controlled very narrow bandpass filters (Q = 20) in a Max patch with faders on a Korg nanoKontrol.

CONCLUSION

In this report, we have described the motivation, methodology, and outcomes of our research project Making Time Together. Collective Experiences of Time in Continuous Ensemble Practice that we conducted during our artistic residency at Studio LOOS.

Working together for such an extended duration at Studio LOOS allowed us to develop two large-scale ensemble pieces that we premiered at two concerts. Each concert was followed by a lively discussion with the audience members that provided important insights into their experiences of space and time during our performances. Many people noted that they felt challenged by the duration of the pieces, but even more so by the unpredictability of that duration. Some movements of the pieces were process-based rather than fully-notated, making it impossible to predict their duration without knowing the details of that process.

Further research and artistic work

different spaces, new pieces

An important outcome of this residency was the development of a solid methodology for creating site-specific performance and installation works based on the acoustic analysis of the space. Following the steps described in section 5.2.2, we will analyse several other concert and exhibition spaces in The Hague and beyond to create ensemble performances and sound installations for them.

future research

One of our major research aims in the future is to develop a qualitative methodology that would allow us to investigate the link between spatial awareness and the experience of time.

Such a methodology would entail a thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews with the performing musicians and listeners, aiming to investigate how the techniques we used to manipulate the perception of the acoustics affect their experiences of time. Such qualitative research can provide deeper insights into the techniques used in this project and suggest pathways for future work.